Former Houston Oilers head coach Bum Phillips once said of Earl Campbell, “He may not be in a class by himself, but it don’t take long to call the roll.” Such was Campbell’s prowess on the field in the late 1970s and 1980s that he is still considered to be one of the greatest athletes ever produced by the state of Texas.

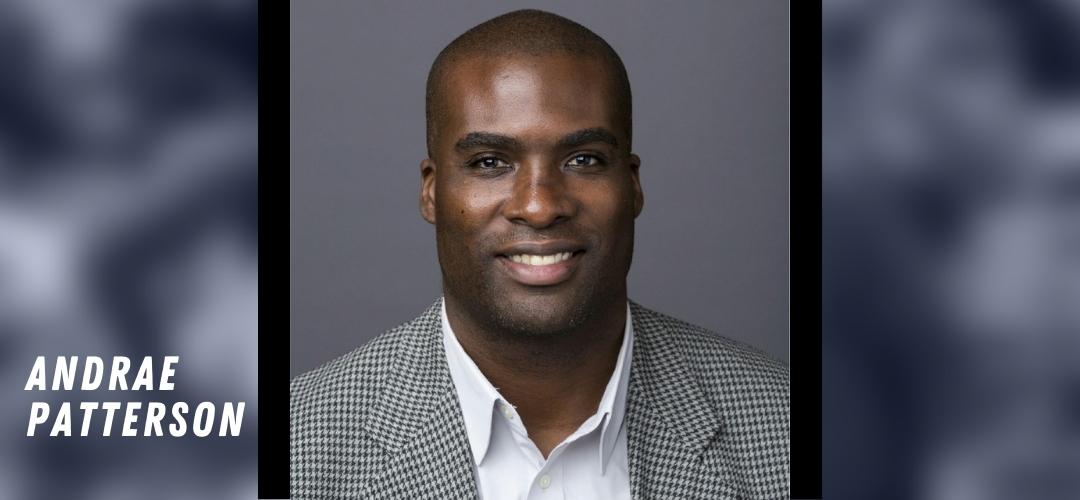

The exact phrase could be used to describe former Cooper High School basketball star Andrae Patterson. He might not be the greatest athlete ever produced by the Abilene ISD, but the list of those in consideration for that title isn’t long.

The list might include former Abilene High and NFL running back Glynn Gregory. Or AHS and Texas Tech wide receiver David Parks. Cooper quarterback and the late Lt. Governor of Oklahoma, Jack Mildren. Or Jon Harrison. Jon Rhiddlehoover. John Lackey. Ahmad Brooks. Jonathan Johnson. Dominic Rhodes. Bob Estes. Scotty Pugh.

But none of those athletes – save for, perhaps, Mildren – brought the kind of star power to Abilene that Patterson did in 1993 and 1994. It was common to show up at Cougar Gym for a practice or game and see college basketball coaching royalty in the stands to watch the man who would become the state’s Mr. Basketball in 1994 and earn Parade All-American honors. Bobby Knight (Indiana), Mike Krzyzewski (Duke), Dean Smith (North Carolina), and Steve Fisher (Michigan), among others, made more than one appearance in Abilene trying to lure the 6-9, 230-pound forward to their campus.

Ultimately, Knight won the recruiting battle for the most highly recruited athlete in the city’s history. Patterson made his way to Bloomington, Indiana, in the summer of 1994 to play for one of the game’s greatest coaches and one of its most controversial.

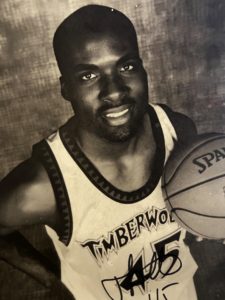

A four-year Hoosier starter, Patterson averaged 11.3 points and 5.7 rebounds per game in 121 contests at IU. He led Indiana to two NCAA Tournament appearances, earning All-Big Ten honors each season. He earned a degree in criminal justice and was the 46th pick in the 1998 NBA Draft by the Minnesota Timberwolves.

He spent two seasons with the T-Wolves before going overseas, where he played nine years, including five seasons in Spain. After retiring, Patterson got into coaching and moved into the Utah Jazz front office in 2015. He then moved to Cleveland from 2017-21 before being hired by the Portland Trail Blazers as Assistant General Manager in January 2022.

He spent two seasons with the T-Wolves before going overseas, where he played nine years, including five seasons in Spain. After retiring, Patterson got into coaching and moved into the Utah Jazz front office in 2015. He then moved to Cleveland from 2017-21 before being hired by the Portland Trail Blazers as Assistant General Manager in January 2022.

Through all of that, he still holds the values taught to him by his parents, teachers, and coaches close at heart: the value of relationships, discipline, and hard work. He’s still as easy-going as a 47-year-old married father of three daughters (ages 22, 19, and 7) as he was as an 18-year-old young man at Cooper.

Patterson and his family – parents Freddie and Brenda and brothers David and Rodney – arrived in Abilene in the late 1980s when Freddie was assigned to Dyess Air Force Base after spending his previous USAF assignment in Iceland. After he retired, the Patterson family stayed in Abilene as the three siblings went through Cooper High School.

Andrae began attending Abilene ISD schools in the sixth grade at Madison Middle School, where he entered as a skinny, 5-foot, 6-inch guard. By the time he left for Cooper, he had grown to 6-5 on his way to 6-9 by the time he had graduated. He had attended some basketball camp before his first year at Cooper, drawing some attention from recruiting coordinators and head coaches.

“I knew then that basketball was going to be an avenue I could use to get a free education,” Patterson said. “But never in my wildest dreams did I think that it would make the impact on my life as it has.”

Patterson recently joined us from Portland for a question-and-answer session to discuss his career, life in Abilene, and how people he met in his adopted hometown impacted his future.

Q: What do you remember about Abilene, and are there some teachers or coaches you can point to along the way at Madison or Cooper who made big impressions on you?

Patterson: “The coaches at Madison had a significant impact on me. Coach (David) Wise, the tennis coach at Madison. Coach Riley Cross coached football and basketball if I remember correctly. I enjoyed the approach both of those men took to discipline because we all knew what to expect. Dennis Harp (former Hardin-Simmons University head coach) also had a big impact on me and my family and was and is a great friend. I remember hating my height the older I got in middle school, but I had an English teacher who always made me proud of it and said it was a gift from God. When I was at Cooper, Mrs. (Cathy) Ashby carried on what that English teacher had told me: to be proud of who I was and use my gifts to bless people. I was also in the Cooper choir under Mrs. (Barbara) Perkins, and she helped me to tap into the arts side of my personality, which I always suppressed because of sports. But she gave me that outlet in the choir, which I really enjoyed. She welcomed me into the class and was able to work around my basketball schedule (practices and games, etc.). I felt bad because it seemed like I was getting special treatment, but the other students in the choir were very understanding.

“Then, of course, the coaches at Cooper were special. I had always wanted to play for head coach (the late) R.M. Currin because my older brothers had played for him. I used to go to Cougar Gym when they were playing, and I would play with the older guys. Coach Currin was a disciplinarian but was also a stickler about a person’s approach to their gifts. But I only got to play under him for one season before he retired. And then Coach (Jack) Aldridge and Coach (Greg) Gober came into my life, and I can’t thank them enough for their influence on me. To this day, Coach Gober continues to impact my life positively. We continue to stay in touch, and I stay in touch with several of my teammates and classmates from Cooper. I had a great experience at Madison and Cooper and in Abilene, Texas, in general, and I will never forget it.”

Q: You brought a lot of national attention to Cooper and Abilene during your last two years, especially. What’s the first thing you think about when going back to those days in your mind?

Patterson: “It’s a little bit like what my parents and Mrs. Ashby reminded me to do: to use my God-given ability to impact others. Hopefully, those days allowed my teammates to be seen by other coaches. Playing in tournaments outside of Texas enabled the city and school to be put on the basketball map and gave exposure to our players and coaches. Maybe those days when we had big crowds at practices or games allowed the city to reap some economic benefit. It was just another opportunity for me to use the ability God gave me to positively impact my community.”

Q: You had so many choices regarding your college; what made you decide on Indiana?

Patterson: “My mom and Coach Knight’s connection was very instrumental. When you’re entrusting your child into somebody’s hands, there’s got to be an alignment, and theirs was regarding both academics and discipline. Those are the things that came into play when deciding on a school. Not that the other schools didn’t have great academics or discipline, but the connection gave my mom a sense that her son would be in good hands.”

Q: Everyone knows the loud and brash side of Bobby Knight; is there another side, and did you see it very often?

Patterson: “A lot of the things that I learned that weren’t publicized with him were how to face adversity and handle the reality of life. A lot of basketball players live a fairy tale life, so he quickly introduced reality to my teammates and me so we would have the proper perspective on life. I learned a lot of life lessons playing for him, and I still check in on him once a month to see how he’s doing.”

Q: You got to live your dream as a professional basketball player; can you describe the highs and lows of that career?

Patterson: “The highs were traveling the United States in the NBA, traveling the world when I played overseas, and seeing how basketball connects many different cultures. The money and status come and go, but seeing how the game brings so many cultures together was fascinating. The connections you make as players and teammates are unique. I keep in touch with so many of those guys. You create a fraternity of brothers, a brotherhood that it’s hard to replicate other than your own family.

“Losing is such a letdown. You make all these sacrifices, so you don’t lose, and then you don’t win a championship; sometimes, that’s hard to get past. But those lows are temporary, and how you bounce back from those matters. Also, being away from your family and the sacrifices you make is always hard. Being away from my family and friends and not being able to have real, genuine connections other than my teammates is tough.

“Sports are great, but they’re not everything. There are different highs in life that I could have reached outside of sports, but it’s been a nice ride to continue to do and be part of something I love. I still have a platform to make a real impact, whether mentoring guys or impacting the office or the locker room. It’s awesome to still be part of a game I love.”

Q: Does the feeling you get after wins and losses differ now from when you were a player?

Patterson: “It’s still the same. Still the same. You try to have an approach of bouncing back from the low. Losses still bring you down, but you can’t stay down.”

Q: What’s your goal in this profession?

Patterson: “It’s always to be part of a championship team, and whatever (front office) title I end up with, being a part of building a championship team would be great. I’ve had the chance to work with some unbelievably talented players in this league, and now I’m working with one of the league’s great talents in Damian Lillard. We’re working hard to build a championship team around him before he retires.”

Q: How has your time as a player framed how you view management-player relationships?

Patterson: “It’s still about doing the right thing and not getting caught up in the business part. That’s one thing I learned from Flip Saunders when I was a player (Saunders was the longtime coach and GM at Minnesota). I’ve never forgotten how he treated players. He would tell them something they might not want to hear but needed to hear because of the business side. It was a reminder of how things function sometimes. It’s not about how you are as a person but about the team. I try to take that approach. You treat players like humans because that’s what they are. You have to think about the decisions and how they impact their lives, children, and family. I’m trying to bring that mindset into what I’m doing now.”